Inland transport infrastructure investment in OECD remains stable at 0.7% of GDP

Spending on inland transport infrastructure showed minimal change in 2016, staying at 0.7% of GDP. However, latest data also shows a reversal in trends of investment per GDP for Australasia, Central and Eastern Europe, and Russia.

- Growth in inland infrastructure investment in Australasia compensated for the reduction in spending per GDP in Central and Eastern Europe, keeping the OECD aggregate level stable.

- The volume of inland transport infrastructure spending in Central and Eastern European Countries decreased 16% in 2016 compared to 2015.

- The Russian Federation shows signs of recovery in inland transport infrastructure investment. Spending per GDP grew slightly to 1.1% while the spending volume increased by 18% since 2015.

- For over three-quarters of Western European countries, the volume of inland transport infrastructure spending declined between 2015 and 2016. However, higher spending in the United Kingdom and Germany helped keep the regional average stable.

- Central and Eastern Europe continued to spend more on road infrastructure and less on railways.

- The share of road infrastructure maintenance spending continued to decline in 2016 for North America, decreasing 4.5% since the 2014 peak.

Investment trends in inland transport infrastructure

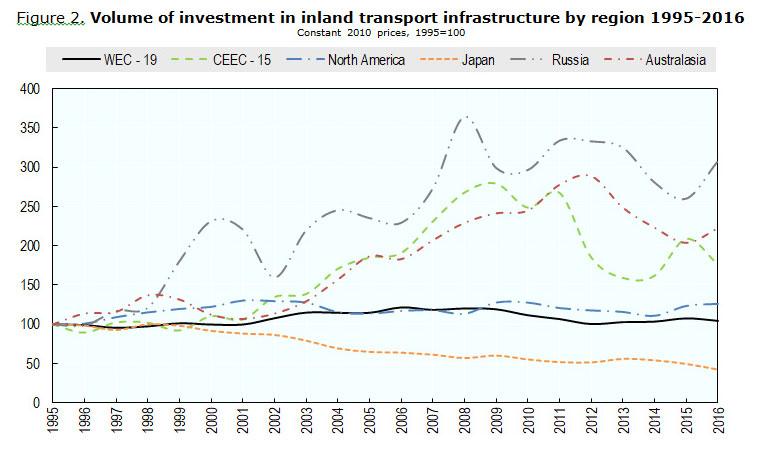

The aggregate spending on transport infrastructure in the OECD has been slowly declining since 2011. In 2016, the gross fixed capital formation (investment) in inland transport infrastructure as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) remained at 0.7% (Figure 1). The slight decrease in investment per GDP in Europe and Japan from 2015 to 2016 was compensated by an upward trend in Australasia, which resulted in negligible change at the aggregate level. In volume terms, there was also a decline in spending on inland transport infrastructure since 2015 in Europe (-5%) and Japan (-14%), whereas Australasia (+9%) experienced growth in volumes (Figure 2). The total volume of spending (after controlling for inflation) for OECD countries in 2016 was 6% lower than in 1995.

Investment in inland transport infrastructure per GDP in Western European Countries (WECs) has had minimal fluctuations over the past two decades. The investment per GDP has been below 1.0% since 1995 and over the years declined to 0.7% in 2016. The volumes of spending on inland transport infrastructure have been more stable in Western Europe than nearly any other region, with only a 5% increase in spending (after controlling for inflation) between 1995 and 2016. Among WECs, Turkey (1.2%) had the highest investment per GDP in 2016. The strongest growth in volumes of spending on inland transport infrastructure since 2015 in the region were recorded by the United Kingdom (+6%) and Germany (+4%) (in constant 2010 prices). The most notable decline in spending volumes occurred in Portugal (-26%), Spain (-22%) and Sweden (-18%).

Among Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs), inland transport infrastructure investment per GDP decreased a quarter of a percentage point to 1.0% in 2016, which remains above the WEC aggregate (+0.3%). Between 2015 and 2016, the volume of spending on inland transport infrastructure declined more for CEECs (-16%) than for any other aggregate or country in Figure 2. Conversely, the long-term trends reveal CEECs spending 76% more on infrastructure in 2016 as compared to 1995 (in constant 2010 prices). Among CEECs, FYROM (2.4%) spent the highest proportion of its GDP on inland transport infrastructure in 2016, followed by Serbia (1.8%) and Romania (1.7%), while Slovenia (0.5%) decreased its investment per GDP by nearly two thirds from 2015 to 2016. Poland and FYROM had the largest increases in volumes of spending on infrastructure since 2015 (in constant 2010 prices), growing 41% and 29% respectively. Otherwise, there were notable declines in the volume of spending since 2015 in Slovenia (-61%), Albania (-51%), Latvia (-48%) and Hungary (-42%).

Similar to recent OECD and WEC trends, inland transport investment per GDP remained stable in North America at 0.6%. The most notable fluctuations in investment per GDP in North America include its decline to 0.5% in 2004 and its peak at 0.7% from 2009 to 2011. North America’s volume of inland transport infrastructure investment in 2016 was 26% above its spending level in 1995 (in constant 2010 prices), including its slight growth in spending between 2015 and 2016 (+2%). The 2016 figures for the United States are preliminary.

Australasia experienced strong growth in inland transport infrastructure investment per GDP since 2001, reaching a peak of 1.7% in 2012. Since then, investment per GDP declined through 2015 before rebounding slightly to 1.2% in 2016. Australia in particular grew a tenth of a percentage point from 2015 to 2016, spending 1.3% of its GDP on inland transport infrastructure. The volume of investment (in constant 2010 prices) also peaked in 2012 and the 2016 data shows volumes rising over 9% since 2015 and over 122% since 1995.

In the 1990s, the inland transport infrastructure investment per GDP for Japan was one of the highest among ITF countries, with the exception of China and four CEECs (Albania, FYROM, Romania, and Slovakia). However, Japan’s investment per GDP has been strongly declining since the early 2000s, which caused a similar albeit smaller decline in the OECD average. Nevertheless, Japan’s investment per GDP (0.9%) in 2016 remained above the OECD average. In volume terms, Japan stands out against the regional aggregates in Figure 2 with a long-term negative trend line, spending 57% less in 2016 compared to 1995 (in constant 2010 prices). India’s inland transport infrastructure investment per GDP reached 1.4% in 2015, which is the latest available data. Investment per GDP in India peaked in 2008 (1.1%), decreased until 2011 (0.8%), and has since had a consistent and strong recovery. Lastly, Russia’s inland transport infrastructure investment per GDP showed strong growth until the financial crisis (1.7% in 2008) after which it decreased through 2015. The 2016 data shows possible signs of recovery, with investment per GDP growing almost two tenths of a percentage point to 1.1%. Indeed, Russia’s volume of inland transport infrastructure investment (in constant 2010 prices) increased 18% between 2015 and 2016.

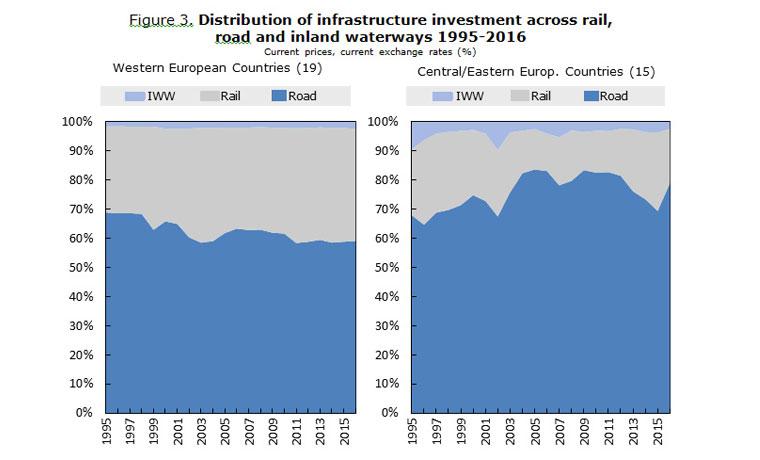

Distribution of spending among inland transport modes

For the past two decades, the distribution of infrastructure spending between roads, railways and inland waterways has been relatively stable in Western Europe (Figure 3). The most notable trend is a shift from spending on roads towards spending on railways. The road-to-rail share of spending changed from approximately 70% to 30% in 1995 to 60% to 40% in 2016. CEECs have had comparatively more pronounced changes in the repartition of investment between inland transport modes. Since 1995, spending shifted away from railways and towards roads, with a reversal of this trend following the financial crisis from 2008 to 2014. The distribution has henceforth shifted back to the pre-crisis trend of more spending on roads and less on railways. From 2015 to 2016, the share of road spending increased 10 percentage points up to 79% of the total inland transport infrastructure investment. Road investment grew most in Poland (+48%), Lithuania (+38%) and FYROM (+29%), whereas railway investments declined in Latvia (-89%), Slovenia (-77%), Lithuania (-61%) and Slovakia (-56%).

Road maintenance

Underspending on road maintenance is a problem in many countries because the gravity of the financial loss in the capital value is often underestimated. For this reason, maintenance spending tends to decrease as soon as there are budget cuts or new infrastructure investment projects. However, case studies have shown that when there is no budget for road maintenance, it can be financially wiser to borrow money and ensure roads are maintained as opposed to putting off such tasks for later years. For similar reasons, prioritising budget allocations for investment over maintenance can have severe long-term financial implications (see "Optimising Road Maintenance" Discussion Paper (2012)).

The share of public road maintenance in total road infrastructure expenditure for OECD countries has been 30% on average over the past 15 years (2002 to 2016) with minimal fluctuations (Figure 4). North America has followed a similar trend slightly above the OECD with a 32% share of public road maintenance spending on average, and a 36% maximum value in 2014. In fact, most countries experienced a peak in share of road maintenance spending in 2014. The share of road maintenance for North America decreased 4.5 percentage points from 2014 to 2016, which is the sharpest decline among the regions in Figure 4. The WEC trend line is relatively stable apart from small peaks in the early to mid-2000s, and it has averaged a share of maintenance spending of 35% over the past 15 years.

While CEECs had the same average share of road maintenance for 2002 to 2016 as the OECD (30%), the region has more pronounced changes in maintenance spending. The highest shares of road maintenance spending for CEECs was in the 2000s (37% in 2001 and 2006), but the region has not surpassed the 30% level since the financial crisis, and was at 27% in 2016.

Capital value of infrastructure

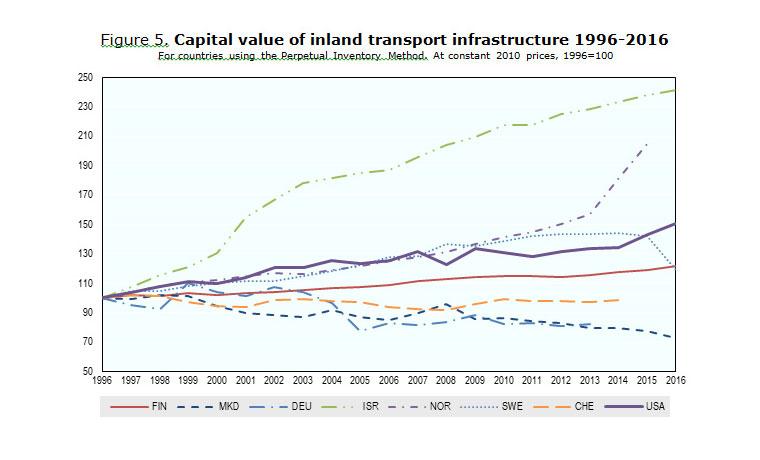

As of 2018, seventeen countries have provided data on the capital value of their transport infrastructure. Since the methodologies are not consistent between the countries, Figure 5 only includes those that are using the Perpetual Inventory Method (PIM) to estimate capital value and that have a sufficiently long time series. That said, the PIM can only provide a rough approximation of this indicator and can vary depending on the accuracy and completeness of the historical cost figures used.

Among the eight countries in Figure 5, Israel has experienced the largest growth in capital value of inland transport infrastructure (in constant 2010 prices), increasing 140% between 1996 and 2016. Norway (+105%), the United States (+50%), and Sweden (+19%) have also increased the capital value of their inland transport infrastructure noticeably since 1996. Sweden diverged slightly from this trend in 2016 when its capital value decreased 23 percentage points compared to 1996 levels. The capital value of Finland’s transport infrastructure has had a slower but consistent growth rate over the past two decades (+21%). Conversely, Switzerland’s level of capital value has hardly changed since 1996 (after controlling for inflation). Furthermore, the infrastructure capital value in FYROM (-27%) and Germany (-18%) has been diminishing since 1996, despite the recent increase in investment spending in these two countries.

Concluding remarks

The trends in this brief are primarily concerned with the evolution of transport infrastructure spending within countries and regions rather than on their levels. Indeed, differences in coverage, definitions and methodologies make it challenging to compare the amounts that countries are spending on transport infrastructure or their levels of capital value. Furthermore, the amount of spending needed to ensure the quality of the infrastructure will depend on the state and age of the existing system and the transport needs of the country. Infrastructure spending can be impacted by geographical constraints, the development of freight movements, and people’s evolving mobility needs and preferences. In addition, the long-term nature of transport infrastructure projects can lead to a lack of timeliness of proposals and completion of said investments, which can prevent spending trends from reflecting countries’ real infrastructure needs. Lastly, underestimations of the financial ramifications for policy makers’ decisions regarding infrastructure maintenance can cause spending to be deferred.

Note: The original version of this text has been amended to exclude maintenance data for Australasia. In Figure 4, Australasia has been removed. Australia is currently revising its maintenance data.

About the statistics

The International Transport Forum statistics on investment and maintenance expenditure on transport infrastructure for 1995-2016 are based on a survey sent to 51 member countries (at the time of the data collection). The survey covers total gross investment (defined as new construction, extensions, reconstruction, renewal and major repair) in road, rail, inland waterways, maritime ports and airports, including all sources of financing. It also covers maintenance expenditures financed by public administrations. Since 2017, the capital value of transport infrastructure is also included in the survey.

The ITF has collected and published data on this topic since the late 1970s. Member countries supply data in current prices. In order to draw up a summary of aggregate trends for selected countries, data has been calculated in euro values at both constant (2010) and current prices. In order to ensure comparability, the Secretariat has devoted a significant amount of effort to collecting relevant price indices in order to make calculations at constant prices. Where available, a cost index for construction on land and water is used. Where these indices are not available, a manufacturing cost index or a GDP deflator is used.

Despite the relatively long time series, these data are often dogged by problems of definition and coverage, which make international comparisons difficult. Also there exists no purchasing power parity-corrected general index for transport infrastructure investment. Finally, indicators such as the share of GDP needed for investment in transport infrastructure, depend on a number of factors, such as the quality and age of existing infrastructure, maturity of the transport system, geography of the country and transport-intensity of its productive sector. Caution is therefore advised for country comparisons of investment data.

Aggregates

Aggregate numbers comprise the following countries, unless otherwise specified:

- OECD: excludes Chile, the Netherlands and Ireland.

- WECs: include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom.

- CEECs: include Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, FYROM, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia.

- North America: comprises Canada, Mexico and the United States.

- Australasia: comprises Australia and New Zealand.

Estimations for missing data

The following data on road or rail investment are estimated using secondary sources: Albania 1995, Bulgaria 1995-2004, Greece 1995-1999 and 2016, Iceland 2016, Italy 2016, Korea 1995-2000 and 2016, Japan 2016, Luxembourg 2016, Malta 2015-2016, Moldova 2015-2016, Montenegro 2016, New Zealand 2016, Norway 2016, Portugal 2011 and 2014-2016, Slovenia 1995-1999, Switzerland 2015-2016, and United States 2016.

This summary covers only aggregate trends in inland transport infrastructure (road, rail, inland waterways). Detailed country data on other items (maritime ports, airports) and detailed data descriptions and a note on the methodology are available here. For more information about this Statistics Brief contact mario.barreto@itf-oecd.org or ashley.acker@itf-oecd.org